|

|

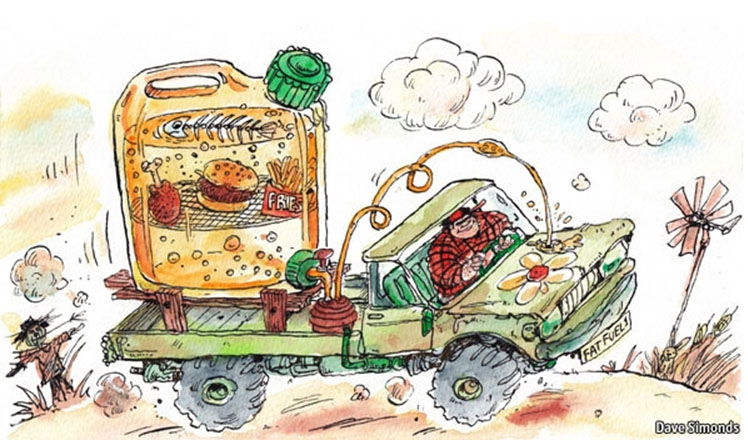

The fat of the land

Green-minded motorists are making car fuel at home, from used cooking oil

Dec 3rd 2011 | from the print edition

DIESEL engines are famously unfussy about what they burn in their cylinders. Indeed, Rudolf Diesel’s original design ran on powdered coal. But even he might have been taken aback by the recipe concocted by Peter Ferlow. Mr Ferlow, who lives in a suburb of Vancouver, British Columbia, is one of the leaders of a growing band of enthusiasts who brew their own car fuel. His diesel engine runs on oil collected from the kitchen of a local pub.

The recipe starts by filtering the breadcrumbs out with a mesh screen. After that you warm the oil up and add sodium hydroxide and methanol. The sodium hydroxide (known as “lye”, in the trade) breaks the oil molecules into fatty acids and glycerol. The methanol reacts with the fatty acids to form esters. Drain away the glycerol. Wash the remainder with water to remove impurities and surplus lye. Drain that water. Then aerate what is left with an aquarium bubbler to drive off the last traces of moisture. The result is 175 litres of finest home-brewed biodiesel—enough to drive Mr Ferlow’s pickup truck for 1,200km (750 miles). And the cost, he reckons, is a mere C$45 (about $44, south of the border) plus two hours of his labour. The oil itself is free. Restaurants are glad to give it away, to avoid the cost of disposal.

That may change. According to Miles Phillips, the head of the Cowichan Energy Alternatives Society, based in Duncan, British Columbia, local demand for veggie-oil fuel is already outstripping supply. Moreover, biodiesel made from restaurant oil can be sold for a tidy profit. On the other side of North America, the Baltimore Biodiesel Co-op, in Maryland, says green-minded drivers are prepared to pay a premium of about 30% over the cost of petroleum-based diesel to fill their cars with biodiesel. The co-operative reports that its sales are up by 20% this year. Eventually, presumably, restaurant owners will want a slice of the action, too. At the moment, though, they seem glad to collaborate for nothing. The co-op can rely on an industrial producer—a so-called “grease puller”—driving a lorry around the area’s restaurants to collect its raw material free. And it plans, starting next year, to buy biodiesel from home producers as well.

Some of these producers rely, like Mr Ferlow, on Heath Robinson lash-ups of their own devising to make their motoring equivalent of hooch. Others use off-the-shelf reactors. Oilybits, a British company, will, for £395 ($620), sell you a device that produces batches of 120 litres of biodiesel—and the firm’s owner, Adrian Henson, is modest enough to admit that many other firms do likewise. The process is not particularly hazardous. Biodiesel esters are not so volatile that they form an explosive vapour (which is why they can be used only in diesel engines, not petrol ones), and though the methanol and sodium hydroxide need careful handling (they are unpleasant by themselves, and truly noxious if allowed to react together), so far the health-and-safety authorities in countries where home-brewed biodiesel is taking off have not stepped in to interfere. Even the taxman generally turns a blind eye. In Britain, which once tried to fine people for failing to pay duty on home-brewed fuel, the tax-free manufacture of up to 2,500 litres a year is now permitted.

Brewing up nicely

If the authorities did ban home esterification, though, enthusiasts who wished to declare independence from the oil companies could go down another route. The advantage of esters is that they substitute directly for petroleum-based diesel fuel. But, with a bit of modification, many diesel engines will run on unesterified vegetable oil, too.

The main reason raw vegetable oils do not normally work in diesel engines is that they are more viscous than standard diesel oil, and thus clog the engine’s fuel-delivery system. Heat them, and that problem goes away—at least in older engines (modern, “common-rail” motors, with high-tech fuel-injection systems, are less forgiving).

A common way of converting a vehicle to run on unprocessed vegetable oil is therefore to fit it with two fuel tanks. A small one filled with petroleum-based diesel keeps the engine running until the car’s radiator has heated up. At that point water is diverted from the radiator into pipes that run through a larger tank filled with vegetable oil. Once this is nicely warm and runny, the driver flicks a switch and the engine starts burning the vegetable oil.

Last year John Shepley, a member of the Baltimore co-operative, converted his 12-year-old sports-utility vehicle to work this way. That cost him about $1,500. But prices are falling as such conversions become more popular. An Oilybits conversion kit costs about $315.

To Greece on grease

Once the conversion is made, the world is your oyster. In August 2008, for example, eight teams set out on a car rally from London. Their intention was to drive across Europe fuelled only by oil scavenged from restaurants. All made it to Athens, the destination, without buying fuel.

Even now, three years later, getting waste oil free is still easy, according to Andy Pag, the rally’s organiser. He has driven more than 30,000km on vegetable oil, in countries as far afield as Mauritania, without once paying for the stuff. There are wrinkles, of course. In place of the screen used by Mr Ferlow, Mr Pag carries a centrifuge (solar powered, naturally) around with him. Before filling up, he puts the oil he has scrounged through this. Food particles and water are spun off as a creamy gunk that he removes with a rag. It takes him about half an hour to purify a tank’s worth of fuel in this way. The chief difficulty, he claims, is keeping his clothes clean.

That, though, is a small price to pay for the warm, virtuous glow which comes from converting waste into motive power. It is cheap, environmentally friendly and, according to Mr Ferlow, even the exhaust gases smell sweeter. |

|